http://rationalfaiths.com/when-you-assume/

http://rationalfaiths.com/multiverse-shapes-laws/

http://rationalfaiths.com/infinite-assumptions/

You've probably heard the saying: "When you assume . . . you make a sum of As and e." For you non-chemists, that would be arsenic plus one electron making an arsenic ion with a charge of negative one. That's not a very stable ion, so it's not really found in nature, thus the saying makes it clear that assuming is pretty unstable grounds for anyone to base life choices on.

You're telling me you heard a different version of that saying? Oh well, you get the point. Except that's not my point.

Everybody assumes. Assumptions underlie all our strongest convictions. No one is exempt. In fact, much of our war of words--the battle some wage between science and religion, between liberal and conservative, between literal believer and symbolic believer, between whole-hearted supporter and loving critic of the Brethren--is an often unrecognized war of assumptions. I want to frame for you, hopefully in a new way, different assumptions we make about the universe and about God. Many of the assumptions about the universe are currently discussed by working cosmologists. Many of the assumptions about God have been discussed for millennia. Most of the assumptions I favor are shaped by Joseph Smith and Mormonism. Some of the assumptions might be testable, soon, and others never will be directly testable. Why might you care about these assumptions? From certain assumptions, Science can disprove God. From other assumptions, Science can't teach you anything about God and Faith. From still others, Science reveals God, or at least aspects of God, to us. Do you want Science and God to be at war? Do you want Science and God to be separate realms of understanding? Do you want Science to prove or disprove God's existence? Do you want Science to reveal God's glory? Do you want Science to assist religion in teaching you to become gods? Do you simply want to know what's true, or what's good? What science does for (or to) religion depends implicitly on assumptions each of us makes about Science and about God.

In the following posts I'm not going to argue much for or against a particular set of assumptions, and I'll only give hints of the consequences of making certain assumptions, or of prioritizing certain assumptions over others. I am going to lay out, as best I can, some of the unproven, and in many cases unprovable, assumptions that we can and must make about the nature of existence. Which assumptions you choose affect such things as your belief in God, your willingness to learn new things, and your prioritization of ethical choices--like how you balance the giving of your time and resources to temple and missionary work or helping the poor. We all make these assumptions, even if we don't recognize or acknowledge them. They shape and are shaped by both our thoughts and our feelings. So take a walk with me through a tangle of assumptions and see if you can't figure out just what you take for granted about reality.

The Outline

I'm going to summarize my next three posts right here. Part 1 will appear over the next two days. Parts 2 and 3 will follow in a month. If I've piqued your curiosity, come back tomorrow for a second helping.- Assumptions about the Universe

- Universe or Multiverse?

- Finite or Infinite?

- Flat or Curved

- Finite numbers of forces and subatomic particles, or not

- Big and Small (and Infinite) Infinities

- Variation among universes

- Something between/surrounding universes, or not

- Assumptions about Evidence

- Only objective, only subjective, or a mix

- What mix is acceptable/admissible

- Assumptions about God

- Limited or unlimited knowledge, power, or presence

- What is the nature of the limitations

- Assumptions about God's purposes

- Assumptions about the best ways to achieve those purposes

- One God or family of Gods

- Nature of God's family

- Human interaction with God

- How involved is God, and how is God involved

- Limited or unlimited knowledge, power, or presence

- Conclusions: We all make assumptions, whether we identify them explicitly or not. Those assumptions bear on such important matters as our belief in God, how we react to new learning, how we feel about good and evil in the world, and how and where we devote our time and resources. For me, it's worth taking the time to explore and evaluate these assumptions consciously, and you are invited to join me or observe my exploration.

The three, nested Klein bottles shown in the image have only one side, like a Möbius strip--the outside is continuous with the inside (although a topologist would tell you that this is only an approximation and that a Klein bottle cannot really be made in our three dimensions--thanks, Dad, for the clarification). Our universe could be flat, or it could have an odd, topological shape like the Klein bottle, only in more dimensions. If this were so, with a powerful enough telescope, we might look off into the distance and see our past selves, just in a mirror image. If you want to learn more about this, I recommend How the Universe Got Its Spots by Janna Levin. It's a fun, accessible read about ideas in modern cosmology. She wrote it so her mother could understand her work.

In this second part of my discussion of cosmic assumptions, I introduce questions about the numbers, shapes, sizes, and compositions of universes. See the introductory post, here.

- Assumptions about the Universe

- Universe or Multiverse?

- Finite or Infinite?

- Flat or Curved

- Finite numbers of forces and subatomic particles, or not

- Big and Small (and Infinite) Infinities

- Variation among universes

- Something between/surrounding universes, or not

- Assumptions about Evidence

- Only objective, only subjective, or a mix

- What mix is acceptable/admissible

- Assumptions about God

- Limited or unlimited knowledge, power, or presence

- What is the nature of the limitations

- Assumptions about God's purposes

- Assumptions about the best ways to achieve those purposes

- One God or family of Gods

- Nature of God's family

- Human interaction with God

- How involved is God, and how is God involved

- Limited or unlimited knowledge, power, or presence

- Conclusions: We all make assumptions, whether we identify them explicitly or not. Those assumptions bear on such important matters as our belief in God, how we react to new learning, how we feel about good and evil in the world, and how and where we devote our time and resources. For me, it's worth taking the time to explore and evaluate those assumptions consciously, and you are invited to join me or observe my journey through this and subsequent blog posts.

Assumptions about the Universe

The purpose of this post is simply to examine a number of assumptions made in the realm of physics. Theological assumptions and the practical and ethical consequences of various assumptions must be saved for later posts.Universe or Multiverse?

Finite or infinite?

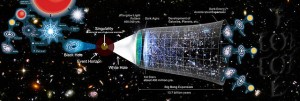

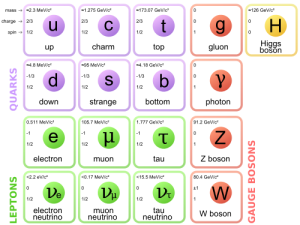

I think most modern people think about space and time as going on forever. Because of this you hear arguments like, "With infinite time and space, everything that can happen, will happen, someplace." This is then used to rebut "Intelligent Design" arguments that human life is too complex to have arisen by chance. It's a patently obvious argument. There are only four forces that govern our entire universe. There is a finite number of subatomic particles that make up everything in our observable universe (ignoring for now dark matter and energy, or at least assuming that they are made of a finite number of things). This means that if time and space go on long enough, literally every combination of the things that make up our universe will be tried by the universe just from randomly combining. One of the most peculiarly Mormon hymns celebrates our knowledge that "there is no end to space", and "no outer curtain where nothing has a place". But this argument is only true if our observable universe, or ones very much like it, are infinite. (Side note: I don't like Intelligent Design. Really. A lot. It makes God way too small for me. I also suspect this argument that everything will happen in infinite time and space is flawed, but that's mostly for a future post.)Flat or curved?

Time and space could be infinite. They could also be finite. It can be argued that time, as we know it, had a beginning with the Big Bang, and that it will have an end with the end of our universe. What about space? Think about our earth. When you go for a long walk, or even drive across country, the world seems basically flat with a bunch of bumps and dips all over it. But we know that if you keep heading in the same direction for long enough you will come back to where you started. The earth is round. The earth is finite. The universe might be round, too. Or it might be a 3-dimensional Moebius strip, or doughnut, or any number of other shapes. The nested Klein bottles (or 3D representation of them) shown in the featured picture show how complex the shape of the universe might be, but living inside it the complexities could be hidden and hard to discern. When it comes to the observable universe, all we know is that it is close to flat for as far as we can see, but there are scientific reasons to ask if the universe might be curved just beyond what we can see, and even theories about what evidence we should look for to answer this question. Time and space in our observable universe might be finite or infinite.How many forces and particles?

Tomorrow

I apologize for cutting this post off in the middle, but I'm at the end of my wife's attention span (for this kind of stuff, anyway), and that is my rule of thumb for post length. Next time I'll continue with the discussion of the multiverse and some thoughts about just how big (and small) infinity might be.In this third part of my discussion of cosmic assumptions, I explain that not all infinities are created equal. I discuss different sizes of infinity, variation among universes, and assumptions we make about evidence. See the introductory post, here, and the follow up post, here.

- Assumptions about the Universe

- Universe or Multiverse?

- Finite or Infinite?

- Flat or Curved

- Finite numbers of forces and subatomic particles, or not

- Big and Small (and Infinite) Infinities

- Variation among universes

- Something between/surrounding universes, or not

- Assumptions about Evidence

- Only objective, only subjective, or a mix

- What mix is acceptable/admissible

- Assumptions about God

- Limited or unlimited knowledge, power, or presence

- What is the nature of the limitations

- Assumptions about God's purposes

- Assumptions about the best ways to achieve those purposes

- One God or family of Gods

- Nature of God's family

- Human interaction with God

- How involved is God, and how is God involved

- Limited or unlimited knowledge, power, or presence

- Conclusions: We all make assumptions, whether we identify them explicitly or not. Those assumptions bear on such important matters as our belief in God, how we react to new learning, how we feel about good and evil in the world, and how and where we devote our time and resources. For me, it's worth taking the time to explore and evaluate those assumptions consciously, and you are invited to join me or observe my journey through this and subsequent blog posts.

Variation among universes

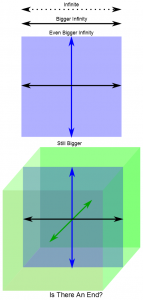

The questions I ended yesterday's post with are ones we have to ask about every possible universe, if there is more than one. Are the numbers of universes infinite, or finite? Is there stuff between the universes, or does nothing exist except where there are universes? Are other universes finite or infinite? Do other universes obey the same laws and have the same subatomic particles as our universe? All of these are currently unanswerable questions, but the ways we think about God, religion, and any number of other things implicitly affirm certain subsets of assumptions and deny the possibility of others. Extrapolating back to our implicit assumptions can reveal inconsistencies in our beliefs. One of the most disconcerting is revealed when we think about there being no end to time and space in our universe--something many of us assume--and also accept the idea that there are multiple universes. Is it even possible for there to be two, infinite universes? If a universe is infinite, doesn't it reach everywhere? And if it reaches everywhere, wouldn't two, infinite universes overlap each other in time and space, and be one universe? The answer to these questions is no.Big and Small Infinities

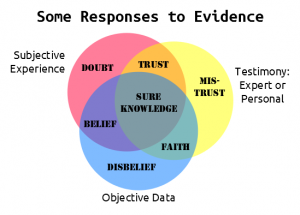

Different sizes of infinities is not an idea that cosmologists or mathematicians struggle with, but the rest of us don't always find it so natural. Infinities come in different sizes. They come in vastly different sizes. Imagine infinitely many libraries. How many books are in those libraries? How many pages? Letters? Ink molecules? Atoms? Getting the idea? But this doesn't begin to show the scope. There are infinities so big that other infinities might as well be zero, when you put them next to each other. In the limit approaching infinity (you probably can't really get there), some other infinities are zero. And there are potentially infinitely many sizes of infinity. Our Cosmos (that's what I'll call the sum of everything that is) might be made up of finities and infinities nested inside of each other, with some being so big that others vanish in insignificance, while others are so close in size that they have to share importance equally. The accompanying figure is intended to help you grasp this idea visually. First take an infinite series of points, sort of like counting by 1's from negative infinity to positive infinity. That's a lot of counting, but it doesn't compare to the number of points in a continuous line spanning that same range. And a line is infinitely smaller than an infinite plane. Add a third dimension, and you are infinitely bigger. Is there an end? I don't know. I think some really smart people would be surprised that their beliefs carry implicit assumptions about infinity that might not be true, or at least don't support their religious (or anti-religious) conclusions. What do your beliefs imply about the infinities of the Cosmos? I'll come back to that question in the future as we think about various understandings of Mormon Gods. Until then, maybe just try to get used to the idea that infinity comes in many sizes.Evidence

I am not a cosmologist. I am not a climatologist. I am not an evolutionary biologist. I am a biophysicist, so I have many of the tools to understand and partially evaluate the explanations of these groups when their claims interest or influence me. So I make judgments about evolution, global warming, and the size and nature of the universe based on expert reports.

I am not a Prophet, Seer, and Revelator. I did not know Jesus or Joseph Smith personally. I am not a theologian, nor am I a historian of religion. I have received answers to prayers and had experiences where I believe truth was revealed to me. My grandparents' grandparents knew Joseph Smith, personally. I've read a fair amount, including a modest amount of theology, philosophy, and history. In other words, I have some of the tools to evaluate the claims of professionals and prophets. I have my own witness, but I also trust my grandfather's testimony who knew and trusted his grandfather, who personally knew and trusted Joseph Smith. It's third hand trust, but it's trust earned by lifetimes of demonstrated goodness, intelligence, and love. I trust these personal, subjective experiences. I claim them as evidence, for me. There are at least two other ways to treat these evidences: claim them as evidence for everyone, or reject them as evidence for anyone. Rejecting them for the purposes of scientific study does not require me to reject them as true, only as objective. What evidence do you accept? What checks and balances have you applied to it? These are questions I think you can't ever stop asking if you aspire to eternal progression.