The following post was published on The Transfigurist on 4/26/2016

The problem of pain is not in its logic. It only defeats false

Gods, or Gods unconstrained by the realities of the nature we live

daily.

The problem of pain is in the gut wrenching

sadness of watching a parent lose a child and thinking of your own

precious children. Of watching a man or woman lose the love of their

life. Of watching families uprooted, homeless and cast upon the whims of

unwilling strangers, thinking of the time you were jobless, homeless,

and on the road with two kids, whatever stuff you could fit in a sedan,

and only safe because of the luck of belonging to a family able to help.

Of visiting your neighbor and smiling and talking like good neighbors

do, but noticing empty cupboards in their tiny, broken, rented home,

knowing your kids--who may be limited in where they go to college by

what scholarships they can get--will be going to college (or its future counterpart), but who knows

where these childhood friends will go from this tiny town with one in

six adults unemployed. Of walking by the friendly old man who is always

out giving candy to kids on Halloween, with a smile and happy words, and

seeing his perpetual rummage sale--and realizing how poor many of your

neighbors must be for his to be even a marginal business--selling stuff

you wouldn't even donate to a second hand store or give to a friend.

That

is the problem of pain. When I don't shut it down or blame it on

somebody so I can pretend it's fair, or at least deserved, I see it for

what it is. It is evil. It hurts. It hurts even when it doesn't hurt us.

We hurt and we rage at injustice. At an unjust universe. At an unjust

God. Yeah, even the Gods that might be real. They aren't stopping the

pain. They aren't fixing the problems. Even if they might fix them

later--balancing out all that wrong on some imagined scale of eternal

justice--that doesn't do squat for here and now. What's unrighteous

about that anger? Anger at big, powerful people, comfortable in their

positions, with enough resources to fix things if they cared enough? You

want to know how I'll react if you tell me that anger's unrighteous?

Probably you don't, but I probably wouldn't react much. Everybody says

dumb things. It's a pain, but usually not much. I've survived worse.

But

when my heart hurts, when I see happy kids with deprived futures, when I

see kind, uncomplaining people with no hope or purpose but to get by

until they die, when I feel irreparable loss--big or small--sometimes I

either cry or scream, or both. Maybe not on the outside, but maybe so.

And it doesn't matter that our Heavenly Parents have an answer.

Especially not since that answer seems to be that the universe is unjust

and uncaring--even the one they live in. It's just pain. There is no

fix. There is no right answer.

One thing that makes it

better for me? We cry together. We scream and rage against that pain

together, and we say NO! NO PAIN HERE! NOT IF I HAVE ANYTHING TO SAY

ABOUT IT! And sometimes we do have a say, so we do something. But sometimes we

don't, so we still scream. We still cry. And we love each other, because

that's all we can do. We create that out of the uncaring universe.

Maybe we have to live forever with the problem of pain. Whatever

explanation we give, it's still pain. But every loving being we make in

this universe--as parents here, or as Parents hereafter--makes the

universe care that much more.

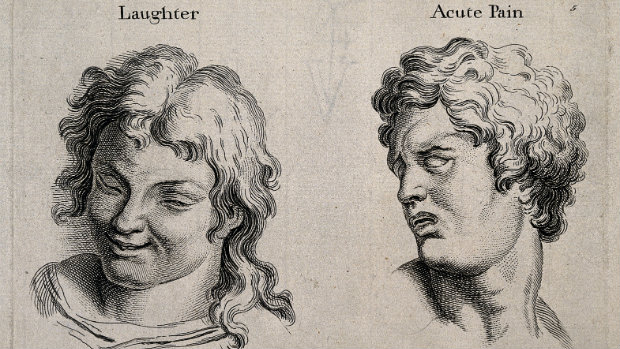

Image Credit: Wellcome Trust

Thoughts on Mormonism, Transhumanism, and reconciling humanity, and original poetry, crafts, and other interests of Jonathan Cannon

Monday, May 23, 2016

Tuesday, May 17, 2016

How I wish my students would read science: a case study on Gender Ideology

I have wondered about the issue of Gender Dysphoria, and when several of my friends and acquaintances posted links to a position statement by the American College of Pediatricians, I was interested. Even as a public LGBTQ ally, I continue to be sceptical of positions that fail to recognize the predominant biological sex binary. I was encouraged as I began reading the ACP position that it distinguished between the clinical definitions of sex and gender, since we often don't understand this distinction because of less specific definitions of the words in common speech. Here I'm going to model stream of consciousness how I read a scientific argument like that made by the ACP, and the kind of thinking I try to model for my Biochemistry students as we work through scientific arguments. We usually don't pick such ideologically controversial topics, but there is still plenty of ambiguity in Biochemistry.

The first point highlighted the predominant sexual binary and its import for continuation of the species. Both facts that concord with my prejudices and understanding. While we don't need every individual to reproduce for survival, we need most individuals to reproduce. But the ACP paper failed to even acknowledge that sex is determined by many more genetic factors than those found on the X and Y chromosome, and they identified all variation from the binary as a disorder. This very black and white oversimplification made me uncomfortable.

At point 2 they recognize the sociological and psychological contributions to gender. Gender is significantly defined by culture and psychology (some have argued completely, but I suspect this doesn't reflect a typically more ambiguous reality). That gender is significantly culturally defined also agreed with my understanding and biases. But once again their statement is black and white, not recognizing any genetic or epigenetic component to gender identity. This increased my discomfort.

The first sentences on point 3 made me uncomfortable--implying a very strong separation between mind and body, psychological and physical problems, that I'm not sure is justified scientifically. In the remainder of the point they identify gender dysphoria as a recognized psychological problem by citing the DSM-V, a diagnostic manual which tends to contain the broad consensus standards by which American psychologists work. This inclined me to believe that gender dysphoria is a problem, and increased their credibility in my emotions.

With point 4 they state something that seems self-evident to me, and a reason I think puberty delaying drugs should be approached with _extreme_ caution. They said that puberty is not a disorder, and delaying it is a disorder. While I still was uncomfortable about the lack of nuance (delaying puberty is sometimes a smaller problem than the alternative), it further inclined me to believe them.

At point 5 I thought, if only 98% of gender dysphoric boys and 88% of gender dysphoric girls resolve their gender dysphoria after puberty, we really shouldn't give them puberty delaying drugs that come with real health risks (points 6-8). But the words "as many as" gave me pause once again. Why are they saying "as many as"? If there is a number, you should look into it. If there isn't a number, you should be dubious of the claims.

Then points 6-8 seemed to be continuing a rhetorical trend that made me uncomfortable. 6 implies that all children who delay puberty will choose to undergo sex changes. It took me a minute to think about it, but while delaying puberty is partly for the purpose of making later sex change less difficult, it is explicitly for the child to have more time to mature and make a very difficult, life-altering decision. Yes, the child is still too young to make a fully mature decision, but at least the child is an older teen rather than a young teen or preteen. And it isn't the puberty delaying drugs with the health risks, as at least one of my friends understood after reading the ACP statement. It's the cross-sex drugs. If this is a scientific statement, they should be justifying these claims with numbers, or make it clear that they are speculating and give justifications for their extrapolations. What is their evidence that children who delay puberty invariably choose sex-change and its associated risks instead of resolving their gender dysphoria and undergoing late, but otherwise normal, puberty? They don't provide links for this, so it looks a lot like a slippery slope argument, and further reason for concern.

Point 7 then compares suicide rates among cross-sex adults over an unspecified period of time with what will happen to children who undergo the same procedure much earlier and after delaying puberty. It is reason for concern, but it is apples and pears (related, but not the same). They do provide a reference to the peer reviewed article, which is good, but they don't even provide a link. And the journal it is published in is in the Public Library of Science. That means it is free online. Why, in such an important statement, would you not take the minute required to provide your readers with a link to the original research? This made me look at the other references more closely. While the references are sound, none of them provide clickable links, despite many of them being freely available online. This is disturbing in an organization that claims professionalism.

But I had only done some of this analysis by the first read through. I had noticed numerous red flags, but all the things that accorded with some of my prejudices, and the proper science-speak on other points, made me inclined to believe the the ACP conclusion in point 8 that using drugs to delay puberty is probably harmful. I wasn't comfortable with calling it abuse--especially since I was aware of a study that found that children who delayed puberty were just as happy in their 20s as their peers who did not, so I had memories that gave pause to claims of abuse. But I though, we probably shouldn't be delaying puberty for most cases of gender dysphoria if it only helps such a small percentage of the already small percentage of children with gender dysphoria.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_College_of_Pediatricians

This group consists of 60-200 members--except that's an estimate because they don't publish how many members they have, just the credentials of a few. That's compared to the American Association of Pediatrics 64,000 members. So it comprises at most 0.1-0.3% of American pediatricians. So this statement is officially supported by only a very small percentage of pediatricians.

I read the follow up clarifications on points 3 and 5. Instead of 2 and 12% of male and female children that don't resolve gender dysphoria, it may be 30 and 50% that don't resolve after puberty. Most likely it's somewhere in between, maybe 1 in 6 males and 1 in 4 females. Where are the recommendations of the ACP for those children? Are those children simply broken and not valuable? The ACP position is clearly that they are broken.

I then went to the "about" page and read it. The ACP makes it clear that they are starting from an ideological position: "We expect societal forces to support the two-parent, father-mother family unit and provide for children role models of ethical character and responsible behavior."

So while I don't think I disagree with any of the facts presented in the ACP position paper, and I agree with the recognition of gender dysphoria as a problem, I am back to believing that the best way to address the problem is to give parents and health care providers tools and choices. They are working directly with the children, so give them best tools available and the right to do their best to help their children as they see fit. Do you imagine the parents care more about a sexual agenda than about their own children? Maybe a few, but I doubt many. I'm sure they will sometimes make mistakes, and that cultural norms sometimes hurt children, but we've been ideologically hurting 2-30% and 12-50% of these children for generations without any possible help for them. I'm glad that doctors are trying to help this small population, and hopeful that over time they will figure out the best ways to do it based on empirical observation more than on ideology.

Initial Impressions

The American College of Pediatricians webpage looked like a valid organization of health care professionals. (I believe it is, even with what I later discovered about the group).The first point highlighted the predominant sexual binary and its import for continuation of the species. Both facts that concord with my prejudices and understanding. While we don't need every individual to reproduce for survival, we need most individuals to reproduce. But the ACP paper failed to even acknowledge that sex is determined by many more genetic factors than those found on the X and Y chromosome, and they identified all variation from the binary as a disorder. This very black and white oversimplification made me uncomfortable.

At point 2 they recognize the sociological and psychological contributions to gender. Gender is significantly defined by culture and psychology (some have argued completely, but I suspect this doesn't reflect a typically more ambiguous reality). That gender is significantly culturally defined also agreed with my understanding and biases. But once again their statement is black and white, not recognizing any genetic or epigenetic component to gender identity. This increased my discomfort.

The first sentences on point 3 made me uncomfortable--implying a very strong separation between mind and body, psychological and physical problems, that I'm not sure is justified scientifically. In the remainder of the point they identify gender dysphoria as a recognized psychological problem by citing the DSM-V, a diagnostic manual which tends to contain the broad consensus standards by which American psychologists work. This inclined me to believe that gender dysphoria is a problem, and increased their credibility in my emotions.

With point 4 they state something that seems self-evident to me, and a reason I think puberty delaying drugs should be approached with _extreme_ caution. They said that puberty is not a disorder, and delaying it is a disorder. While I still was uncomfortable about the lack of nuance (delaying puberty is sometimes a smaller problem than the alternative), it further inclined me to believe them.

At point 5 I thought, if only 98% of gender dysphoric boys and 88% of gender dysphoric girls resolve their gender dysphoria after puberty, we really shouldn't give them puberty delaying drugs that come with real health risks (points 6-8). But the words "as many as" gave me pause once again. Why are they saying "as many as"? If there is a number, you should look into it. If there isn't a number, you should be dubious of the claims.

Then points 6-8 seemed to be continuing a rhetorical trend that made me uncomfortable. 6 implies that all children who delay puberty will choose to undergo sex changes. It took me a minute to think about it, but while delaying puberty is partly for the purpose of making later sex change less difficult, it is explicitly for the child to have more time to mature and make a very difficult, life-altering decision. Yes, the child is still too young to make a fully mature decision, but at least the child is an older teen rather than a young teen or preteen. And it isn't the puberty delaying drugs with the health risks, as at least one of my friends understood after reading the ACP statement. It's the cross-sex drugs. If this is a scientific statement, they should be justifying these claims with numbers, or make it clear that they are speculating and give justifications for their extrapolations. What is their evidence that children who delay puberty invariably choose sex-change and its associated risks instead of resolving their gender dysphoria and undergoing late, but otherwise normal, puberty? They don't provide links for this, so it looks a lot like a slippery slope argument, and further reason for concern.

Point 7 then compares suicide rates among cross-sex adults over an unspecified period of time with what will happen to children who undergo the same procedure much earlier and after delaying puberty. It is reason for concern, but it is apples and pears (related, but not the same). They do provide a reference to the peer reviewed article, which is good, but they don't even provide a link. And the journal it is published in is in the Public Library of Science. That means it is free online. Why, in such an important statement, would you not take the minute required to provide your readers with a link to the original research? This made me look at the other references more closely. While the references are sound, none of them provide clickable links, despite many of them being freely available online. This is disturbing in an organization that claims professionalism.

But I had only done some of this analysis by the first read through. I had noticed numerous red flags, but all the things that accorded with some of my prejudices, and the proper science-speak on other points, made me inclined to believe the the ACP conclusion in point 8 that using drugs to delay puberty is probably harmful. I wasn't comfortable with calling it abuse--especially since I was aware of a study that found that children who delayed puberty were just as happy in their 20s as their peers who did not, so I had memories that gave pause to claims of abuse. But I though, we probably shouldn't be delaying puberty for most cases of gender dysphoria if it only helps such a small percentage of the already small percentage of children with gender dysphoria.

Looking Further

I still had to relieve my concerns with the red flags. I made myself look further. The comments of another interested party on Facebook helped, but it turns out it isn't hard to discover something about the ACP by a simple Wikipedia search:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_College_of_Pediatricians

This group consists of 60-200 members--except that's an estimate because they don't publish how many members they have, just the credentials of a few. That's compared to the American Association of Pediatrics 64,000 members. So it comprises at most 0.1-0.3% of American pediatricians. So this statement is officially supported by only a very small percentage of pediatricians.

I read the follow up clarifications on points 3 and 5. Instead of 2 and 12% of male and female children that don't resolve gender dysphoria, it may be 30 and 50% that don't resolve after puberty. Most likely it's somewhere in between, maybe 1 in 6 males and 1 in 4 females. Where are the recommendations of the ACP for those children? Are those children simply broken and not valuable? The ACP position is clearly that they are broken.

I then went to the "about" page and read it. The ACP makes it clear that they are starting from an ideological position: "We expect societal forces to support the two-parent, father-mother family unit and provide for children role models of ethical character and responsible behavior."

Scientific Merit

At this point, I would hope it is clear to any of my students that the ACP position statement is of dubious scientific quality. Before concluding that my beliefs are scientifically justified, I should be going to other sources. The Wikipedia article suggested a likely one, so I looked it up. Here it is, Just the Facts about Sexual Orientation and Youth from the American Psychological Association. Just having skimmed a few parts, it's a much more useful read--broadly informative, more nuanced, and less dogmatic in its claims. Clearly more focused on caring for the child rather than asserting an absolute societal norm.So while I don't think I disagree with any of the facts presented in the ACP position paper, and I agree with the recognition of gender dysphoria as a problem, I am back to believing that the best way to address the problem is to give parents and health care providers tools and choices. They are working directly with the children, so give them best tools available and the right to do their best to help their children as they see fit. Do you imagine the parents care more about a sexual agenda than about their own children? Maybe a few, but I doubt many. I'm sure they will sometimes make mistakes, and that cultural norms sometimes hurt children, but we've been ideologically hurting 2-30% and 12-50% of these children for generations without any possible help for them. I'm glad that doctors are trying to help this small population, and hopeful that over time they will figure out the best ways to do it based on empirical observation more than on ideology.

Tuesday, May 3, 2016

Interacting with the Disaffected from Mormonism

I continue to be a believer in Mormonism. I don't think many people who

know me question this, even if as practicing Latter-day Saints they

think I could be more committed to my ward or the LDS church, even if

they question my understanding of doctrine or faith, or what it means to

follow God, or even if they know my sins and failings. Doubters and

unbelievers don't hesitate to identify me as believing, if they think

about it. Yet I have spent some significant time and energy over a

period of years interacting with and learning from many who question and

criticize Mormonism at different levels, some who leave or have left,

and a smaller fraction of those who have become critics of Mormonism or religion generally. A friend asked me for advice on interacting with friends who are also critics of Mormonism. Here's my advice:

Do your best to muddle through as lovingly and sanely as possible.

But now for an answer that is really a personal reflection. What do I try to do? What do I succeed in doing? I have several answers. Here is a list as they come to mind:

Do your best to muddle through as lovingly and sanely as possible.

But now for an answer that is really a personal reflection. What do I try to do? What do I succeed in doing? I have several answers. Here is a list as they come to mind:

- I spent time getting to know what critics were talking about. I read critical and apologetic material, and I read scholarly material. I read and enjoyed the softer scholarship of Hugh Nibley (I like his peer reviewed stuff on the ancient world really well, too), as well as the alternative framings of Mormonism provided by writers like Eugene England and some scientist saints in stories and testimonies like those posted in Mormon Scholars Testify, and before that in the book Expressions of Faith (My dad's testimony is included. His and Paul Cox's are two of my favorites.)

- I also read some "New Mormon History" somewhat randomly. I didn't know people who could recommend the best stuff. Now you can find great recommendations like this top 10 list discussed in Rational Faiths podcasts.

- I listened to lots of podcasts to learn more about LDS history and doctrine. In the process I learned a lot about LDS culture, and the intimate details of the stresses people feel as members of the LDS church. It's worth listening to people's stories. Perhaps worth more than listening to the interviews with experts, but I loved many of those, too.

- I started engaging with the disaffected. I like this term, because I think it describes so many of us so well. We have lost affection for the LDS church, perhaps Mormonism generally, and maybe even religion and God. The degree varies. I still feel a lot of affection for all of these things, but not as much love and trust of leaders and institutional structures. But I am much more than acquaintances with people along a multidimensional spectrum of disaffection.

- I don't engage much, now. I engaged most when I was trying to figure out what I thought on dozens of issues. Now it's mostly just with loved ones.

- I try to be willing to validate emotions. I'm convinced emotions are real and matter. When a person feels betrayed or angry, that is really how they feel. There are real reasons for it or causes of it. Their perception is a valid reality whether I share that reality or not. I don't get to say people are wrong for experiencing their own experiences.

- I try to be informed and validate factual observations that are unflattering to Mormonism. If you are my close friend, I might even tell you I think something you think is evil is evil.

- I try to assume the best of every party--present or not, public figure or private individual. I want people to think I'm thoughtful, loving, principled, etc. So yes, I spin news and arguments to make everyone look as good as I can.

- I share and write criticism when I feel like I need to. But when it's criticism, I sit on it for a while to see if I really feel like saying it and if I can say it in more understanding ways.

- I share and write apologetics when I feel like it. I hope I'm rarely insensitive, but I like explaining ideas I think are valuable and comparing them with alternative ideas.

- Mostly with all of this I just tell my story. Sometimes my story is an attempted logical argument. Sometimes it's an emotional plea. But I try to show real respect that others can have different, morally justified, stories.

- When I disagree and feel like it needs to be said--maybe because I imagine there is an impressionable audience--I try to disagree pleasantly and not worry about winning a debate. I try to bow out considerately and let others have the last say (except to maybe show that I heard and understand what they said)--most of the time. I'm convinced that's as effective as debating for influencing people in most settings.

- I post my thoughts mostly on blogs where people have to actually go a little out of the way to read my full thoughts. I love it when people listen to me or read my words, but they need space for their words, too. They also need space to not care about me. Especially since, you know, I'm a white, heterosexual, educated, lifetime Mormon, American male. That doesn't mean my voice doesn't count, but my life is pretty well represented in the Bloggernacle. I need to be willing to step out of the spotlight, however much I love an audience.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)