My third biblical studies book review is

An Introduction to New Testament Christology by Raymond Brown. I love it, so this is going to be a very long review. I'm going to focus on the approaches we take to scripture as illustrated in the book. If you want to know what else it talks about, you'll need to go read the book. I give it two thumbs up. Now on to my disjointed review.

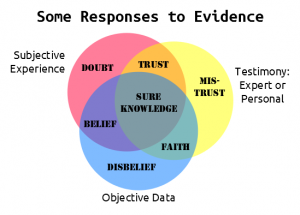

Raymond Brown begins quite early to describe different approaches to understanding Christ, or Christology. Besides identifying High and Low Christology (High discusses the divinity of Christ, while Low rejects or ignores it), Brown sweepingly categorizes approaches into five categories: Nonscholarly Conservatism, Nonscholarly Liberalism, Scholarly Liberalism, Bultmannian Existentialism, and Scholarly (Moderate) Conservatism. Of course these don't capture all the nuances that Brown is aware of, but they describe some trends and camps that it can be useful for the student to understand. I'll provide a few excerpts about the various groups.

The Divisions

Nonscholarly Conservatism

Even

though the Gospels were Written

some 30 to 70 years after the ministry of Jesus, they are assumed to

be verbatim accounts of what was said in Jesus’ lifetime.

In other words, everything in the Gospels is assumed to be exactly what happened. While most of us Mormons aren't fundamentalists--particularly not regarding the Bible--this is an approach we often implicitly take, unless we have somehow been trained or trained ourselves to look more critically. Fortunately, it works for understanding lots of good things.

Nonscholarly Liberalism

At

the opposite end of the spectrum is the view that there is no continuity

between Jesus’ self-evaluation and the exalted Christology

of the NT documents. Such liberalism dismisses NT christology as

unimportant or as a distortion, and has often been closely associated

with the thesis that Jesus was just an ethical instructor or social reformer

who was mistakenly proclaimed to be divine by overenthusiastic

or confused followers (with Paul sometimes seen as the chief

instigator).

These two camps have had much rather unfortunate interplay that we see in many, if not most, public presentations of religion.

On

the conservative side, as I have explained, many Protestants reflect

the reaction of an earlier generation to the destructive aspects of

radical biblical criticism; and most Catholics remain unaware that

their church and its scholars have moved beyond views taught in

catechism in the first part of the 20th century. On the liberal side, there

is a tendency to invoke what the latest scholars are supposedly saying,

according to reports in the media. Despite the differences among

scholars I shall desciibe below, their efforts pay tribute to the truth

that christology is so important an issue for religious adherence that

one should not express judgments without seriously looking at the

evidence.

Scholarly Liberalism

This

differs from nonscholarly liberalism in several important ways.

It recognizes that the NT is shot through with christology from beginning

to end and that its authors claimed far more than that Jesus

was a moralizer or a social reformer. Nevertheless, as the classification

“liberalism” implies, it does not accept the high christological evaluations of Jesus in the NT as standing in real continuity with

his self-evaluation. In short, high christological evaluations are regarded

as mistaken.

I should explain what Brown means by continuity. He means, did Christians in the time of Paul believe the same things as Christians in the time of Jesus, and did Jesus actually teach the things (and mean the things in the way they were interpreted) that the first Christians believed? The question is, did Christian thought change (it did), and if so, how did it change?

Scholarly liberalism has also influenced many who lean toward the views of nonscholarly liberalism. This is the kind of thinking that is pervasive in internet discussions of Mormonism, with varying degrees of usefulness.

Somewhere

in between nonscholarly liberalism and scholarly liberalism is the view of those who have read scholarly liberal works (the weaknesses

of which they do

not subject to suflìcient criticism) but whose view of Jesus is

really determined more

by their reaction to the suffocating fundamentalism in which they

were raised.

I'm sorry to say this flatters neither the individual nor the culture that raised them.

Returning to the scholarly views, Brown makes this observation regarding their beliefs:

The

historical Jesus

was, in fact, a preacher of stark ethical demand who challenged the

religious institutions and the false ideas of his time. His ideals and

insights were not lost because the community imposed on its memory

of him a christology that turned him into the heavenly Son of

Man, the Lord, and Judge of the World-indeed, into a God. Without

that aggrandizement he and his message would have been forgotten.

But if in centuries past such a christological crutch was necessary

to keep the memory of Jesus operative, in the judgment of the liberal

scholars that crutch could now be discarded. Modern scholarship,

it is claimed, can detect the real Jesus and hold onto him without

the christological trappings.

Brown, himself, doesn't fall into this camp (he's a Catholic Monk), but he takes their scholarship seriously and has sifted through it--I like to think on behalf of those of us who believe and are unwilling to wade through the sludge of unwarranted assumptions made by unbelievers. My thanks go out to him for this work.

Bultmannian Existentialism

It's hard for me to describe this coherently, although Brown and Sanders both taught me something about it in their respective books. Bultmann (and some of his contemporaries and followers) accepted the methods of the 19th and early 20th century liberal scholars, but rejected their rejection of high christology. They downplayed, however, the literalness of much of the NT message in favor of emphasizing the importance of what we Mormons might describe as the Atonement in modern life. It doesn't really matter if certain events or sayings literally happened or came unmodified from Jesus. The challenge to find salvation applies to us, today, and Jesus and his message (whether from Jesus or from the early Christians) are powerful messages to help humanity. Will we accept the great things God has done for us, rather than rely on our own powers as advocated by scholarly liberalism? (That's my best attempt at translating what I learned, but I warn you it may be seriously flawed)

Scholarly (Moderate) Conservatism

. . . they posit a christology in the

ministry of Jesus himself. They would be divided on whether that

christology was explicit or implicit. Explicit christology would involve a

self-evaluation in which Jesus employed titles 0r designations already

known in Jewish circles. Implicit christology would relegate such

titles and designations to early church usage but would attribute to

Jesus himself attitudes and actions that implied an exalted status

which was made explicit after his death.

Explicit christology, which seemed to

be fading, got new life in the late 20th century. “Son of Man”

remains a title that many scholars think Jesus used of himself.

“Messiah” remains a title that others may have used of him during his

lifetime, whether or not he accepted the designation.

These scholars may only be conservative relative to liberal scholars, but the ongoing differences of opinion among scholars about such fundamental views of Christ is something to keep in mind. When people claim "broad scholarly consensus" on a New Testament issue, unless they are talking about something very specific and limited, it seems like good advice to take some care in accepting the assertion--even if it comes from an expert. To quote Brown:

This survey shows that scholarship has

come to no universally accepted positions on the relationship

of Jesus’ christology to that of his followers, except that the extreme

positions on either end of the spectrum (no difference, no continuity)

have fewer and fewer advocates.

Topics

Jesus' Omniscience

One of the most interesting discussions early in Brown's book was that of Jesus' knowledge of things. Since Jesus was God, did he know everything during his mortal life? As Mormons we don't find it hard to answer no because Joseph Smith put Jesus' growth in wisdom and stature, line upon line, into the Doctrine and Covenants, giving us a second witness on the subject. The New Testament doesn't provide such a simple solution. Brown illustrated how what is shown in the New Testament can be used to answer this question. He showed passages where Jesus displayed knowledge beyond what could have been available to his senses, and passages where Jesus seemed to lack knowledge. I'm still getting used to how scholars like Brown and Sanders collate and interpret the various evidences in such potentially meaningful ways. Brown doesn't answer the question, but he does show the New Testament evidence that one must deal with to come up with a intellectually responsible answer, and gives some hints as to how different people have answered the question. Here is part of Brown's summary:

This chapter has reviewed a range of

the ordinary and religious knowledge manifested in the Gospel

accounts of Jesus, and throughout there were signs of limitation.

Those who depend on a theological a priori argument that, because

Jesus was “true God of true God,” he had to know all things, have

a difficult task in explaining such limitations. They must resort to

the thesis that he hid what he knew and deliberately manifested

limitations in order not to confuse or astound his hearers. That

explanation limps, for his hearers are portrayed as confused and

amazed in any case. Since there is at least one recorded statement

where Jesus says that the Son does not know, most biblical scholars

will not accept such an explanation and will query the validity of

the a priori claim for omniscience.

On the other side of the picture, even

in the partial range of Jesus’ sayings considered thus far, there

is real difficulty for those who assume that Jesus presented himself

as just another human being. Under (A) we saw traditions that Jesus

manifested knowledge beyond ordinary human perceptiveness, and under

(B) We saw Jesus’ authority in interpreting Scripture and his

absolute conviction that God would punish Jerusalem and the Temple

and make him victorious despite his sufferings. All this corresponds

well to the repeated evaluation of him during his lifetime as a

prophet, one of those specially sent by God to challenge the

covenanted people. Probably most a priori approaches to Jesus from

the “true man” side of the spectrum would accept “prophet” as

a historical self-estimation of Jesus, but would argue that he could

have been no more than that. However, in the last elements that we

discussed in this chapter (B ##8-10) there were already indications

that the truth may have been more complicated. Jesus saw himself as

so important that rejection of him (not only of God’s message)

would constitute the cause for divine action against Jerusalem and

the Temple. Indeed he was remembered as saying “I will (or am able)

to destroy.” Jesus claims that he is not only to be made victorious

(translated by his followers, perhaps post factum, in terms of the

resurrection of the Son of Man) but also to have a final role (as the

coming Son of Man) when God completes what was begun during his

ministry. This goes beyond the claims of OT prophets and manifests a

uniqueness in Jesus’ self-estimation. He is not simply one of those

whom God sends but the one to bring God’s plan to completion.

For the believer, like me, in Jesus' divinity, it appears that the Gospels really are filled with evidence that Jesus was limited in mortal ways. For the nonbeliever who would explain away Jesus' divinity by saying he never claimed it for himself, you will have to explain away more than just a couple of disconnected sayings. It appears that actually reading the New Testament limits the possible scenarios more than many people would like.

Brown's Approach

One of the main reasons I love Brown's book is his approach to Christology. He says it thus:

In opting for a desciptive approach to

the NT evidence without embracing “cannot have” or “must

have” presuppositions that stem from emphasizing one side ofthe “true

God, true man” issue, I am not denying that proponents of such

presuppositions have something to Contribute to the overall

christological picture. Objections raised by philosophers and scientists

on one side and corollaries drawn by theologians on the other must

be considered seriously, but they must not be allowed to

determine what the NT reports.

In other words, the evidence doesn't care if you believe it or not. Christ was reported by both his adherents and his enemies as having performed notable miracles. That is evidence, whether you believe the miracles really happened or not. You can look for naturalistic explanations of the miracles (Jesus didn't really multiply the loaves and fishes, that's just a story introduced later), but you have to actually explain the evidence and not just wish it away. Conversely, you can't just pretend that contradictory passages in the Gospels aren't contradictory. You have to face the evidence that is there and not pretend that some of it doesn't exist, or doesn't matter, just because it doesn't agree with your presuppositions. This doesn't mean that Brown doesn't allow wiggle room for honest differences in belief. What he doesn't allow is arbitrary picking and choosing of what he himself will examine when trying to understand the Christ of the New Testament. The implicit invitation is for us to do likewise and really examine the books that we've had in front of us all our lives.

Brown is intimately aware of a number of prejudices found in approaches to New Testament christology. He highlights a couple more in his chapter on Jesus' views of his own mission:

We come now to the most difficult area

for the discernment of Jesus’ own christology-difficult because of

the lack of evidence. After Jesus’ death Christians reflected

intensely on Jesus’ identity, particularly in terms of titles that

expressed their faith: Jesus is . . . Messiah/Christ, or Lord, or Son

of God, or Son of Man, or even God (APPENDIX III). . . here we

confine ourselves to the very limited evidence for Jesus’

application of the titles Messiah, Son of God, and Son of Man to

himself or his acceptance of them when applied by others.

Before I begin, some cautions are in

order. First, were we to decide that Jesus did not use or accept one

or the other of these titles, that would be no decisive indication

that Christians were unjustified interpretative combination of

several passages. Yet any affirmation that all this development must

have come from early Christians and none of it came from Jesus

reflects one of the peculiar prejudices of modern scholarship. A

Jesus who did not reflect on the OT and use the interpretative

techniques of his time is an unrealistic projection who surely never

existed. The perception that OT or intertestamental passages were interpreted to give a

christological insight does not assign a date to the process. To

prove that this could not have been done by Jesus, at least inchoatively, is surely no less difficult to prove than that it was done by him. Hidden behind an attribution to the early church is often the assumption

that Jesus had no christology even by Way of reflecting on the

Scriptures to discern in what anticipated way he fitted into God’s

plan. Can one really think that credible?

Brown passes lightly over the prejudice of many believers, this time. We must be careful and realize that there isn't much solid evidence regarding what Jesus thought of himself. Brown is less gentle with the scholarly prejudice that assumes all high christology postdated Jesus' life and words. Once again, here is the double edged sword of detailed New Testament study.

Interesting Excerpts

Jesus' claim to authority:

Worthy of note is that the oracles are

uttered with first person authority, “I say to

you,” quite unlike the prophetic custom of having God speak (“The Lord

says . . .”: Isa 1:24; Jer 2:12; Hosea 11:11; Amos 3:1 1; etc.). Why

Jesus can speak with such personal authority is never explained

in the Synoptic Gospels; indeed that silence over against the

prophets’ explanation that word of God came to them implies a very high

christology wherein the authority to make demands in God’s

name simply resides in Jesus because of who he is.

This certainly never was obvious to me. It seems you can convincingly argue that Jesus' not claiming authority from God as earlier prophets did is, when put together with the things he said and did, a claim to greater authority that the prophets of old.

The resurrection:

The

developing sequence from the way

in which Jesus presented himself during his lifetime to the

way in which those who believed in him presented him afterwards is

more complex than such a sequence would be for any other figure. In

the case of others one might find an adequate explanation for

development in logical, psychological, and other familiar diagnosable

factors; but in the tradition about Jesus a unique factor massively

intervened that goes beyond human diagnosis, namely, the

resurrection. In the publicly received tradition of Israel (i.e.,

what a later generation would dub canonical) no one had hitherto been

raised from the dead to eternal life, and so this claim of faith

about Jesus had an enormous import. Besides heralding a victory over

death, God’s raising of Jesus to glory vindicated both the origin

and the truth of the authority/power that he had claimed and

manifested. His followers who saw the risen Jesus realized that he

was even more than they had understood during his public ministry.

The resurrection, therefore, makes it very difficult to explain away

as romanticized creation the more explicit christology attested after

the resurrection.

I always thought of the resurrection as one of those things that, while there are plenty of supposed witnesses, it's something there really isn't much proof for, and that scholarship could choose to ignore--even if I wished they couldn't. What I'm seeing as I begin to read is that scholars have to take the resurrection seriously. As a minimum, they have to deal with the fact that early Christians believed it happened. As a maximum, they have to explain why the tomb was empty, and they have to do that by guessing. The historical sources (if they say anything) seem to universally agree that it was empty, but nobody can produce the body to prove how it was emptied. Brown doesn't go into this, but there are entire popular books on it (that I'm not inclined to read) that have collected the historical evidence. I still think it's not provable, and even if we proved Christ was risen, that wouldn't prove everything else we believe, but I was surprised to see how central central the resurrection is to all biblical scholarship, not just the religious.

The tension between Servant and King

All the Gospels present a Jesus who was

clearly Messiah, Son of Man, and Son of God (and sometimes

specifically Lord) during his public ministry. Gospel readers

immediately know this because they are made party to a revelation

connected to the baptism of Jesus where God speaks from heaven and

calls him “My beloved Son” (Mark 1:11; Matt 3:17; Luke 3:22178).

In the two-step resurrection chrístology discussed at the end of the

preceding chapter, the ministry of Jesus from the baptism to the

cross Could without difficulty be presented as one of lowliness (Phil

2:7 speaks of Jesus in “the form of a servant”) since exaltation

came only with resurrection. In ministry christology, however, where

exalted status and lowly service coexist, there is inevitable

tension.

Let us consider one way in which that

tension was handled by the evangelists. A resurrection christology

passage, such as Acts 13: 33, can apply Ps 2:7 to Jesus without

qualification: “You are my son; today I have begotten you.” The

Synoptic baptismal designation, “My beloved son; with you I am

well pleased,” has modified Ps 2:7 by combining

it with words (italicized) from the description of the Servant in Isa

42:1. By this combination the evangelists indicate that to understand

Jesus as the messianic king during his public ministry one must

recognize that he was simultaneously both the

Messiah/Son and the Servant who did not

cry out (Isa 42:2) and was pierced for our offenses, bearing the

guilt of all (Isa 53). Since it is not clear that in preChristian

Judaism the ideas of the Messiah and the Suffering Servant had been joined,

Jews who did not accept Christian claims might well point out that a

Messiah whose life terminated in suffering was a drastic Change of

the concept of the expected anointed Davidic king. Christians would

reply that Jesus threw light on the whole of the Scriptures and

showed how once separate passages should be combined.

Beyond this common approach, in

describing the ministry of Jesus individual NT writings treat

differently the tension between the exalted Messiah/Son image and the

lowly Servant; and this difference contributes greatly to the

distinctiveness of each of the four Gospels.

Mark preserves the greatest amount of

lowliness by describing a precrucifixion ministry in which no human

being recognizes or acknowledges Jesus’ divine Sonship. Thus the

christological identity of Jesus is a “secret” known to the

readers (who are told at the baptism) and to the demons (who have

supernatural knowledge; Mark 1:24; 3:1 l; 5:7) but not to those who

encounter him or even to those who follow him as he preaches and

heals. Mark 8:27-33 shows how little even Peter, the most prominent

disciple, has understood Jesus. He has come to recognize that Jesus

is the Messiah, but his understanding of messiahship would not allow

Jesus to suffer. He is like the blind man of 8:22-26: Jesus has laid

hands on the man, and he has come to partial sight (people look like

trees); but it will take further action by Jesus before he sees

clearly. If Mark’s readers or hearers wonder why Jesus does not

reveal his christological identity clearly to his disciples, the

scene of the transfiguration in Mark 9:2-8 supplies an answer. There

Jesus is transfigured before them and the glory that has been hidden

throughout the ministry shines forth brightly.

The Gospels are easy to read. Thank goodness, or I never would have read them the few times I have. Apparently I missed a few things in my reading, though.

Jesus gives Judas permission to go off

to betray him (13:27-30). When he says “I am,” the party

of Roman soldiers and Jewishpolice that have come to arrest him

fall backwards to the ground(18:6). The disciples of the Johannine

Jesus do not flee as he is arrested; he arranges for them to be let

go so that it may be seen that he has not lost any of them (18:8-9).

This Jesus does not die alone and abandoned; not only is the Father

always with him (16:32), but at the foot of the cross stand his

mother and the beloved disciple (19:25-27)-symbols of a believing

community that he has gathered.

Therefore, knowing that he has

accomplished all that the Father has given him to do and has completed the

Scripture, he can decide “It is finished” and give over his spirit

(19228-30). Obviously, as last words, this is a far cry from the “My

God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” of Mark and Matt.

These examples suffice to show that

despite the four evangelists’ agreement that during his ministry

Jesus was already Messiah and Son of God, the way in which they

balance that with a picture of him as rejected and misunderstood varies so

that very different Gospel pictures of Jesus emerge. For those who

accept the later church confession of Jesus as true God and true

man, the different picture in each Gospel, while supporting overall

that confession, gives its peculiar insight into one or the other

side of that mystery: Mark, for instance, more insight into Jesus as

true man; John, more insight

into Jesus as true God. No one Gospel

would enable us to see the whole picture, and only when the four

are kept in tension among themselves has the Church come to

appreciate who Jesus is.

I always thought the evangelists described the same events. I still accept it as a matter of trust that they did, and that they each came fairly close to things that really happened, but even if I accept that, they were telling stories with agendas, and I can learn more if I can see their agendas.

Conclusions

Once again, I have both found new thoughts to enrich my understanding, and plenty of room to remain the kind of believer I am. Scholarship places limits on what I can responsibly accept as true. I need to adjust to those limits. I can work on that. Still, an understanding of Christ arrived at without the evidences of the Book of Mormon and modern scripture fails to address the divine Jesus I know. I look forward to when a Mormon Raymond Brown tackles the New Testament and helps me see Jesus with new eyes. If you know of one, tell him or her to get writing, please.